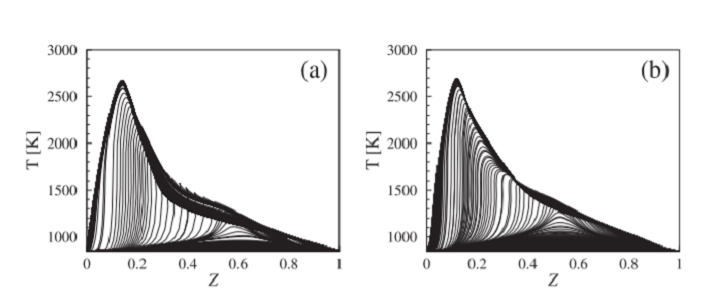

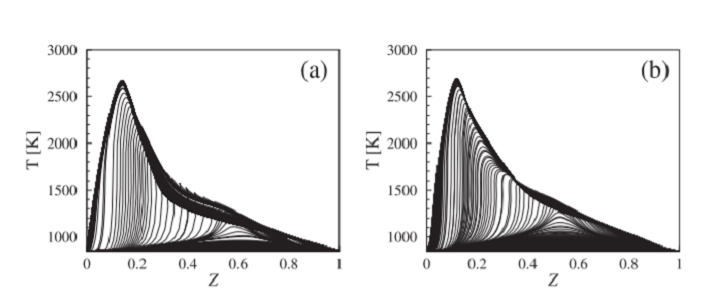

Plots of the temperature profiles in the mixture fraction space during the ignition event for (a) DME0 and (b) DME50.

Reproduced with permission from reference 1 © 2018 Elsevier

Highly fuel-efficient new engine designs could significantly reduce the environmental impact of vehicles, especially if the engines run on renewable nonpetroleum-based fuels. Ensuring these unconventional fuels are compatible with next-generation

engines was the aim of a new computational study on fuel ignition behavior at KAUST.

The team, led by Hong Im at the KAUST Clean Combustion Center, investigated the ignition of methanol-based fuel formulations. “Methanol is considered a promising fuel from both economic and environmental standpoints,” says Wonsik Song,

a Ph.D. student in Im’s team. Methanol can be produced renewably as a biofuel or by a solar-driven electrochemical reaction that makes methanol from carbon dioxide. However, pure methanol fuel is ill-suited to the latest engine designs.

Conventional gasoline engines use a spark to ignite the fuel. Some modern gasoline engines can switch to compression-ignition mode, operating like a diesel engine under certain conditions to maximize fuel efficiency. But methanol is not reactive enough

for compression ignition, says Song. “Our approach is to blend a more reactive fuel, dimethyl ether (DME), with methanol to make a fuel blend that is usable in compression-ignition engines and provides better combustion efficiency than the

spark-ignition counterpart.”

(From l-r) Efstathios Tingas and Wonsik Song discuss the results of the study with Professor Hong Im.

© KAUST

The team used computational analysis to investigate methanol-DME combustion chemistry. Because combustion is too complex to efficiently simulate in full, the researchers first generated a skeletal model of the process in which peripheral reactions were stripped away.

“Starting from the detailed model, including 253 chemical species and 1542 reactions, we generated a skeletal model comprising 43 species and 168 reactions that accurately describe the ignition and combustion characteristics of methanol and DME,” explains Efstathios Tingas, a postdoctoral member of Im’s team.

The researchers showed that DME dominated reaction pathways during the initial phase of ignition and was a highly effective ignition promoter. They also examined the effect of increasing the initial air temperature to simulate the hot spots that might develop inside the engine. “At high temperatures, DME actually retards ignition slightly because DME chemistry relies on the formation of some highly oxygenated molecules, which are inherently unstable at higher temperatures,” Tingas says. However, at high temperatures, the methanol itself becomes highly reactive. They also studied DME’s effects on ignition timing.

“This study serves as a basic guideline to study the ignition of methanol and DME blends in combustion engines with compression ignition modes,” says Song. The next step will be to perform more complex simulations that incorporate the effects of turbulence on fuel ignition, he adds.